Four drivers of frontline employee satisfaction and business results: United Kingdom spotlight

Executive summary

Frontline employees make up 45% of the UK workforce — approximately 16.7 million people1 — yet many face low wages, restricted benefits, and limited opportunities for growth. Women, who hold 43% of these roles,2 are particularly affected, often receiving fewer development opportunities.3 As a result, nearly half (46%) of frontline employees consider quitting on tough days,4 and 40% cite pay as their top reason for leaving.5 This equates to roughly 6.9 million frontline employees at risk of not showing up to work tomorrow, placing immense strain on businesses and the wider economy. The cost of inaction is steep — an estimated £283.6 billion in potential turnover expenses.6 But wages alone don’t tell the full story — 52% of frontline employees feel advancement is out of reach, and only 49% believe they receive adequate training to progress.7

We surveyed 2,939 frontline employees and managers in the United Kingdom8 across a range of industries9 and quantified their satisfaction with five aspects of job rewards and growth opportunities: base pay, pay increases, benefits, job growth and development opportunities, and advancement.

Through our analysis, we found that respondents fell into two distinct profiles based on their level of satisfaction.10

Critically, our ability to classify employees into these two categories allows us to examine what policies, processes, and conditions drive employee satisfaction with each of the five aspects of job rewards and opportunities. Because women are disproportionately present in the moderately dissatisfied group, any efforts to increase gender equity in frontline workplaces will be inherently deficient if organisations don’t pursue the strategies identified in this research.

Business results surge when employees are more satisfied

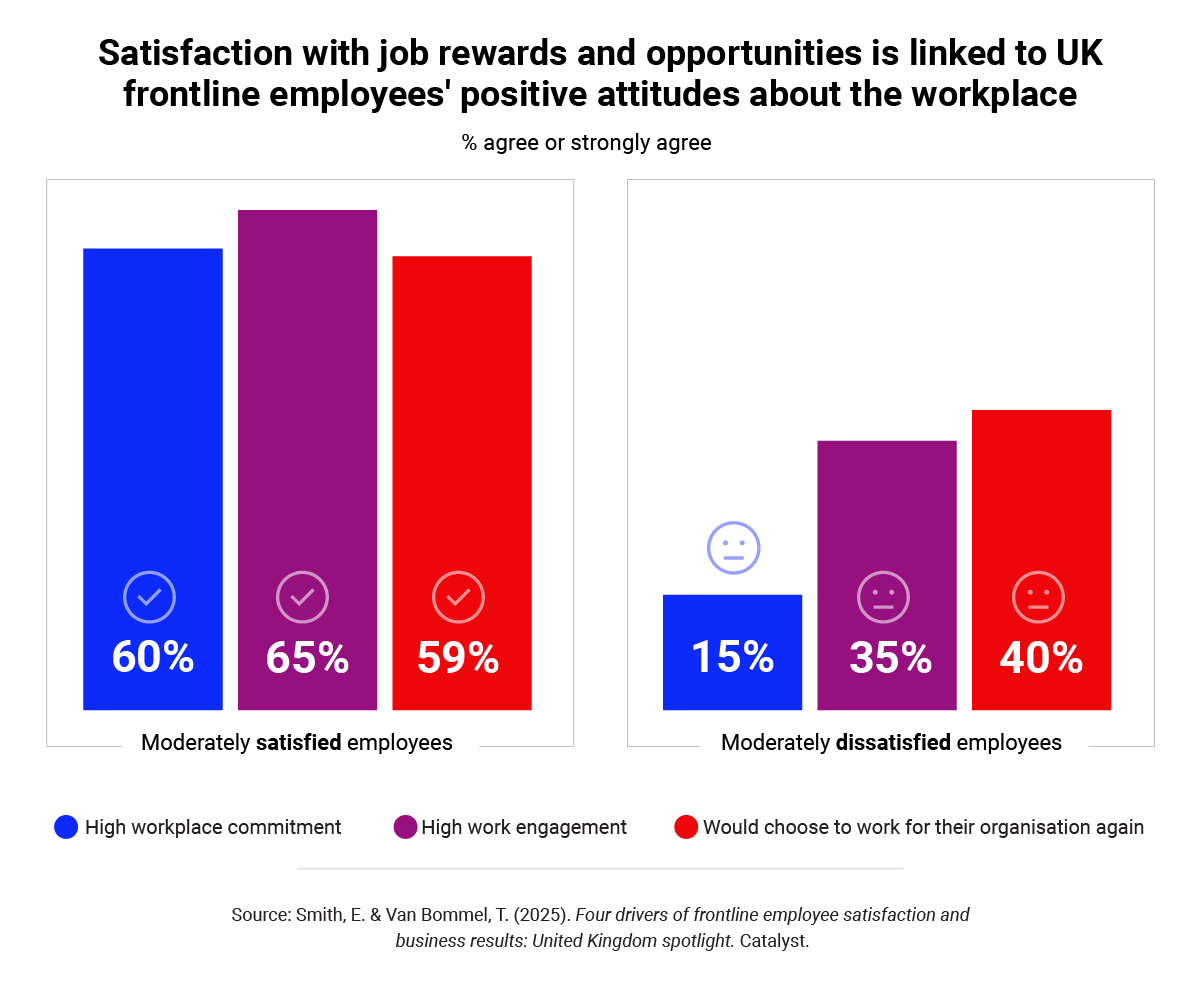

As frontline employees’ satisfaction with their job rewards and growth opportunities increases, we observe a striking surge in organisational commitment, engagement,11 and intent to stay.12 Notably, 60% of moderately satisfied employees report being highly committed to their workplace — almost nine times the rate of those who are moderately dissatisfied (15%).13

This reinforces that job rewards and development opportunities are not just perks but essential drivers of retention and performance. Only by addressing these multiple pain points will companies be able to improve retention and elevate the frontline employee experience — especially for women, who continue to have the lowest wages and fewest opportunities for growth and improvement.

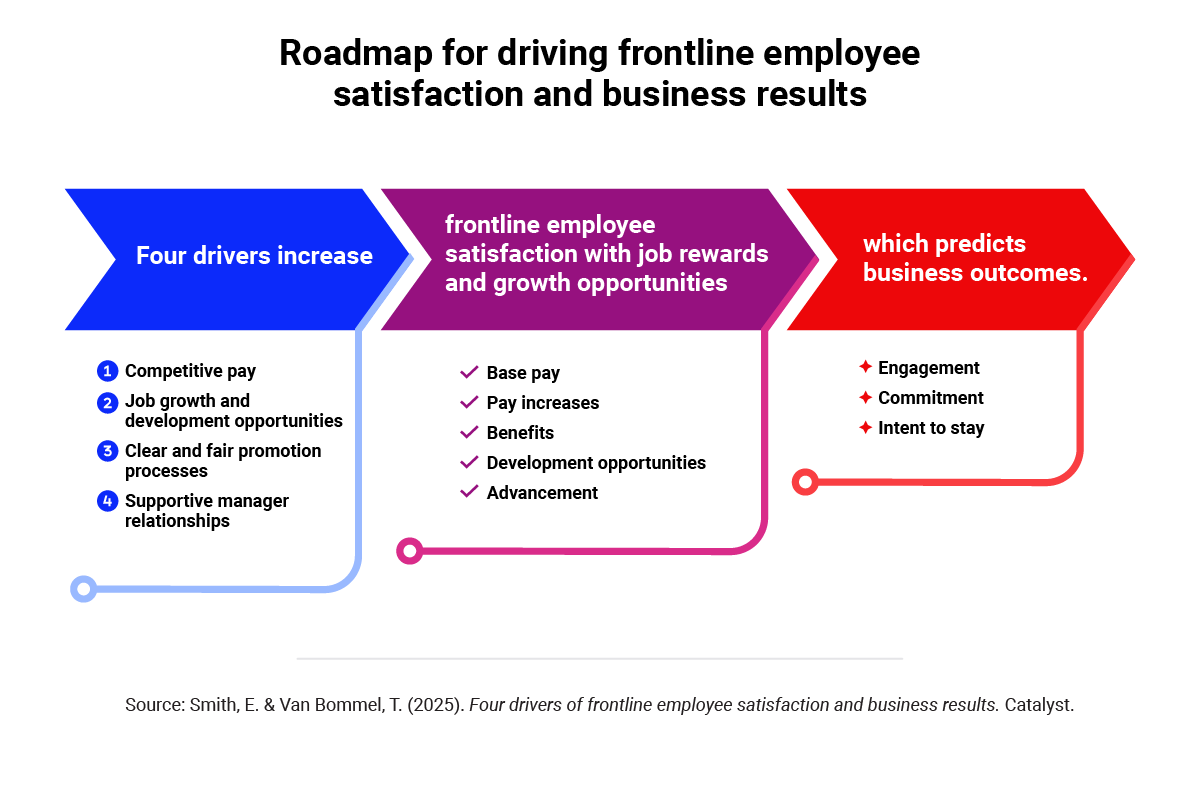

Four drivers of employee satisfaction with job rewards and growth opportunities

Our data also show that frontline leaders should take four actions that will increase satisfaction with job rewards and growth opportunities and ultimately enhance frontline employee engagement.

Driver 1: Competitive pay

Done right, this strategy could yield a 5x return on investment.

Key finding: Higher base wages are merely the starting line. Substantial and strategic pay rises are essential to elevate satisfaction levels of frontline employees — an absolute necessity for fostering retention, engagement, and contentment across frontline roles — and a foundational strategy for fostering long-term financial stability and retention.

Digging deeper: In today’s tight labour market, competitive base pay is the foundation for attracting and retaining frontline talent. Yet, many frontline employees — particularly women14 — still do not earn a true living wage, making financial insecurity a persistent challenge.15 Regular wage increases help employees achieve a living wage, but our data show that it’s the baseline wage itself — not just merit- or performance-based rises — that has the most significant impact on satisfaction. As baseline wages rise, so does employee satisfaction,16 which in turn drives productivity and reduces turnover. This influential sequence delivers measurable financial benefits for organisations.

However, not all employees experience financial growth equally. Pay progression varies widely, and company-wide wage rises remain rare17 — just 11% of moderately dissatisfied and 14% of moderately satisfied employees received one. Performance-based rises are more common among the moderately satisfied employee group,18 but overall, our data show that the most effective strategy for boosting satisfaction is ensuring employees earn a meaningful wage. Women, however, remain overrepresented in lower-wage roles,19 and therefore overrepresented in the moderately dissatisfied group, distanced from the pay levels most strongly linked to higher satisfaction, engagement, and intent to stay.

The bottom line? A strong base wage is the most powerful lever for increasing employee satisfaction with pay and benefits — an investment that yields significant returns.

Although the desire to make more money is commonplace, these employees are barely earning a living wage. People taking home just enough to cover basic expenses are less likely to feel economically secure or engaged at work. For hourly frontline employees, financial stability begins to improve around £25 per hour,20 while for salaried employees, the tipping point lies around £40,000 annually.21 These thresholds mark the transition from the moderately dissatisfied group to the moderately satisfied — but they do not represent financial security, let alone thriving.

Satisfaction levels often plateau once these thresholds are reached, highlighting that financial stability alone is not enough. Greater satisfaction — and with it, higher engagement, commitment, and intent to stay — is linked to additional factors, such as job growth, skilling and development opportunities, and support from both teammates and managers. Organisations should consider these income thresholds as a baseline rather than an endpoint, ensuring that employees' financial wellbeing is complemented by pathways for advancement and a supportive work environment.

What level of pay increase results in employees feeling both financially secure and satisfied?

A pay rise of £5 per hour (£10,400 annually per employee) moves frontline employees closer to economic security and could yield a 5x return on investment, with every £1 spent on pay increases saving approximately £5 in reduced attrition costs.22

Just as important as the pay itself is laying out and communicating a clear path to higher wages, complemented by benefits and development opportunities. Most employees don’t expect immediate, large pay increases, but knowing there is a structured way to get there fosters engagement, commitment, and long-term retention.

Some frontline employees may still rely on government support, such as Universal Credit,23 housing assistance, or council tax reductions. This can create a "benefits trap," where rising wages lead to reduced benefits, sometimes offsetting financial gains. As a result, employees earning above a living wage may feel more stable than those earning less, but many are still navigating financial uncertainty.

Driver 2: Job growth and development opportunities

One in five employees at risk of turnover could be retained through this strategy.

Key finding: For companies looking to boost retention, strategically bundling job growth and development opportunities is a practical move that improves not only employee satisfaction but also loyalty and performance.

Digging deeper: To achieve financial stability, employees need more than adequate pay — they also want to know that they can advance, learn new skills, be challenged at work, and receive growth and development opportunities. Our data show that access to skilling and development opportunities are pivotal in shaping frontline employees’ satisfaction,24 with those who are moderately satisfied seven times25 as likely as moderately dissatisfied employees to report frequent access to opportunities to learn new skills, partake in job-shadowing and mentorship programmes, and expand their role.26

Yet, class mobility remains a significant barrier in the UK, where certain roles are still largely restricted to those with higher education qualifications. Research shows that low-income students who attend university are four times more likely to experience upward mobility; but for those who do not, career advancement opportunities are often limited.27 Expanding access to these roles — by focusing on skills and experience — could be a major lever for change, especially since 72% of our sample does not have a degree. But this requires providing employees with the opportunity to grow.

Indeed, access to development and growth opportunities was a key differentiator between employees who are satisfied and those who are not.28 By every measure, there is a significant gap in access to opportunities for growth, including in:

Without clear pathways for growth, many employees face stagnation. Fewer than half (48%) believe advancement is possible at their company, and only 49% feel adequately trained.36 This lack of development is a key driver of disengagement, with nearly half (48%) of disengaged employees citing it as a concern, and 20% of those planning to leave in the next year highlighting a desire for job growth.37 Closing the gaps in access to essential growth opportunities — from mentorship programmes to moving from part-time to full-time roles — both empowers employees and signals that they are valued contributors to the organisation.

Driver 3: Clear, fair, and individual-centered promotion processes

This strategy can boost employee satisfaction by at least nine times.

Key finding: Organisations that clearly communicate the factors that drive promotions —including timing and the necessary skills and training — and work with employees to prepare them for promotion can make a significant impact on employees’ career trajectories, satisfaction, and loyalty.

Digging deeper: In addition to development opportunities, frontline employees want consistent and clear promotion processes,38 along with an individual-centred approach to promotion,39 which together play a crucial role in shaping satisfaction with job rewards and growth opportunities. The data show stark differences in access — a twelve-fold boost for consistent and clear processes,40 and a nine-fold boost for individualised promotion processes41 — across the satisfaction profiles, demonstrating the strength and value of these practices in promoting a satisfied and engaged workforce. Without clear, fair, and individualised promotion processes, organisations risk disengagement and dissatisfaction, particularly among frontline employees who often face unique challenges in navigating career advancement.

What defines clear, fair, and individual-centred promotion processes?

Employees want their organisations to provide clear, consistent information about how promotion decisions are made. This includes well-defined standards and criteria, as well as open communication about decision-making processes. When promotion pathways are transparent, employees perceive the system as fair and promotion achievable, fostering greater trust and engagement.

Beyond clarity, employees value promotion processes that consider their personal needs, preferences, and career goals. This tailored approach not only enhances satisfaction but also empowers employees to take an active role in their own development, reinforcing their connection to the organisation.

Driver 4: Supportive manager relationships

Managers who support employee growth, development, and life-work balance can triple employee satisfaction.

Key finding: Managers are an employee’s main conduit to the larger organisation. When they are perceived as fair, supportive of growth, and aware of people’s competing life and work responsibilities, they can combat employee disengagement and help boost satisfaction.

Digging deeper: For frontline employees, manager support is a critical — and often underestimated — driver of satisfaction. When managers ensure fair access to opportunities,42 actively invest in the growth and development of team members,43 and provide the flexibility44 needed so job demands allow for work-life balance,45 the impact is striking. Employees who feel moderately satisfied with their jobs are more than three times as likely to perceive fairness in resource distribution46 and almost six times as likely to feel supported in their professional development compared to those who are moderately dissatisfied.47 Balance also plays a major role — moderately satisfied employees report nearly a 40 percentage-point advantage in job demands aligning with personal needs, along with significantly greater access to flexible working policies.

These forms of managerial support are especially important in addressing persistent workplace barriers. Nearly 70% of employees, and an even higher proportion of women (73%), feel uncomfortable discussing pay increases with their managers, while almost half of women employees (46%) lack confidence that they will receive development opportunities suited to their skills.48 By actively fostering career growth and enabling better work-life balance, managers don’t just shape day-to-day experiences — they play a pivotal role in elevating overall job satisfaction.

Take action

The four drivers outlined above comprise 21 unique actions, policies, or practices. We quantified which are the most effective, finding that the following five tactics have the greatest impact on employee engagement, retention, and satisfaction,49 in turn driving the most significant results and strongest return on investment for organisations.50

Action: Increase organisational transparency in how decisions are made

Action: Train managers to follow fair procedures in decision making

Action: Provide clear and accessible promotion pathways for employees at all levels

Action: Ensure managers apply policies consistently to all employees

Action: Design processes to balance job demands to ensure employees can meet their life needs and responsibilities

As the UK government prepares to introduce new employment laws,52 there is a crucial opportunity for organisations to rethink and enhance the rewards and benefits offered to frontline employees. Our findings underscore the importance of prioritising fair pay, comprehensive benefits, skill development, and clear advancement opportunities — key factors that directly influence job satisfaction, engagement, and retention. These upcoming legislative changes provide a timely catalyst for businesses to align their strategies with a more inclusive and equitable approach, ensuring frontline workers are not only supported but empowered to thrive. By investing in the abovementioned areas, organisations can foster a stronger, more committed workforce that drives long-term success.

Explore more regions

Methodology

Recruitment and sample

Participants were full-time frontline employees (entry-level, first-level manager, or supervisors) recruited through a panel service company. After obtaining informed consent, participants completed a 20-minute online survey.

Procedure and analysis

Participants were asked about their experiences in their workplace. Specifically, we asked questions about positive job conditions and opportunities for job improvement that they may (or may not) have experienced, as well as about a range of company practices that impact employees’ financial situations.

Participants were also asked demographic questions such as their race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and caregiving status. Participants were also asked questions about their financial situation, like how much money they earn, the amount of any recent raises or promotions, and their ability to make ends meet.

We employed several statistical analyses to investigate the impact of fair pay, comprehensive benefits, skill development, and clear advancement opportunities on frontline employee satisfaction, engagement, commitment and intent to leave. We conducted exploratory factor analysis, a two-step cluster analysis, ordinal regression, linear regression, and relative importance analysis.

All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS version 25 except for relative importance analysis, which was performed using Python version 3 in JupyterLab. All results presented in this report were significant at p < .01 unless otherwise noted.

Demographics

Note that participants could skip demographic questions, so totals may not equal 100% or total sample size.

| Total # of respondents |

Age | Gender | Industry | Race / ethnicity | Sexual orientation | Frontline role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,939 | 40 Average age |

49% Women |

36% Retail and wholesale |

76% White |

88% Heterosexual |

33% Non-managerial roles with no supervisory responsibilities |

|

|

18 – 75 Age range |

50% Men |

16% Finance and insurance |

9% Asian |

10% Asexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, or queer |

30% Non-managerial roles with supervisory responsibilities |

|

|

<2% Other genders |

14% Manufacturing |

9% Black |

|

37% First line or frontline managerial roles |

|

|

|

|

|

12% Construction |

5% Multiracial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

11% Hospitality |

<1% Latine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9% Transportation and warehousing |

<1% Arab, Iranian, Turkish, Romani, or a mix of these |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2% Utilities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<1% Mining, quarrying, oil and gas extraction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<1% Water supply and waste management |

|

|

|

Satisfaction profiles by rank, gender, and industry

| Rank (# total) | Moderately dissatisfied | Moderately satisfied |

|---|---|---|

| Non-managerial roles with no supervisory responsibilities (n = 968) |

60% | 40% |

| Supervisor (non-managerial roles with supervisory responsibilities) (n = 884) |

51% | 49% |

| First line, first level or frontline managerial roles (n = 1,087) |

40% | 60% |

| Gender (# total) | Moderately dissatisfied | Moderately satisfied |

|---|---|---|

|

Man (n = 1,457) |

48% | 52% |

| Woman (n = 1,432) |

51% | 49% |

| Other gender (n = 43) |

63% | 37% |

| Industry (# total) | Moderately dissatisfied | Moderately satisfied |

|---|---|---|

| Retail and wholesale (n = 1,051) |

54% | 46% |

| Finance and insurance (n = 473) |

39% | 61% |

| Manufacturing (n = 400) |

55% | 45% |

| Construction (n = 339) |

43% | 57% |

| Hospitality (n = 320) |

49% | 51% |

| Transportation and warehousing (n = 261) |

57% | 43% |

| Utilities (n = 59) |

36% | 64% |

| Water supply and waste management (n = 20) |

50% | 50% |

| Mining, quarrying, oil and gas extraction (n = 16) |

38% | 63% |

About the authors

Ellie Smith, PhD

Ellie Smith, PhD, is a developmental cognitive neuroscientist and thought leader specializing in the science of behavior change, translating data into powerful tools for impact at both individual and systemic levels. As an EMEA-based Research Director at Catalyst, she brings a global lens to her work, applying expertise in diversity, equity, and inclusion, research methods, and advanced statistics to explore how cultural and organizational contexts shape workplace experiences in the rapidly evolving world of work.

Tara Van Bommel, PhD

Tara Van Bommel, PhD, is a social psychologist with expertise in stereotyping and prejudice, nonconscious bias, and intergroup relations. At Catalyst, Tara leads the Research team and brings her background in advanced statistics to develop solutions that create meaningful systemic change in the workplace and more positive workplace experiences for women across intersections of identity.

How to cite: Smith, E. & Van Bommel, T. (2025). Four drivers of frontline employee satisfaction and business results: United Kingdom spotlight. Catalyst.

Endnotes

- Catalyst Labor Economist review of Office of National Statistics 2021 & 2023 data collected and analysed in June 2024.

- Catalyst Labor Economist review of Office of National Statistics 2021 & 2023 data collected and analysed in June 2024.

- Growth and access to development opportunities remains a significant challenge, particularly for women. Only 25% of women frontline employees say their manager has outlined steps toward their promotion, compared to 30% of men, and just 18% have been connected with a mentor, versus 25% of men; Pace, L. (2022, March 8). Gender imbalance at work continues. Quinyx.

- Perspectives from the frontline workforce: A UKG global study. (2024, October). UKG.

- The state of the UK frontline workforce 2024 report. (2024). Quinyx.

- Out of approximately 16.7 million frontline employees, 46% report considering leaving their roles, which equals 6.9 million. Approximate turnover cost per frontline employee is £41,102. As such, 6.9 million x £41,102 = £283.6 billion as an estimate of the at-risk cost to organisations that do not ensure sufficient wages, benefits, and advancement and growth opportunities.

- From unsung heroes to quiet quitters. (2024). Flip.

- We surveyed 2,939 frontline employees and managers in the United Kingdom in a variety of industries, including retail (n = 911, 31%), wholesale (n = 140, 5%), hospitality (n = 320, 11%), manufacturing (n = 400, 14%), construction (n = 339, 12%), finance and insurance (n = 473, 16%), mining, quarrying, oil and gas extraction (n = 16, <1%), utilities (n = 59, 2%), water supply and waste management (n = 20, <1%), and transportation and warehousing (n = 261, 9%). Our sample was almost equal parts cisgender women (n = 1,432, 49%) and men (n = 1,457, 50%), with some representation of other genders (n = 43, <2%). Around three-quarters of the respondents were White (n = 2,213, 76%) and our sample included representation from other racial and ethnic identities as well: Asian (n = 268, 9%), Black (n = 252, 9%), Latine (n = 8, <1%), Arab, Iranian, Turkish, Romani, or a mix of these (n = 17, <1%), and multiracial employees; (n = 155, 5%). Most respondents identified as heterosexual/straight (n = 2,572, 88%), and our sample represented other sexual identities as well (e.g., asexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, or queer employees (n = 304, 10%). The average participant age was 40 years old, and ages ranged from 18 to 75. Most respondents were Millennials (n = 1,223, 42%), 22% were Gen Z (n = 640), around a quarter were Gen X (n = 808, 28%), and the rest were Baby Boomers (n = 268, 9%). A third of the respondents were in non-managerial roles with no supervisory responsibilities (n = 968, 33%), roughly a third were in non-managerial roles with supervisory responsibilities (n = 884, 30%), and the rest were in first line or frontline managerial roles (n = 1,087, 37%). Note that participants could skip demographic questions, so totals may not equal 100% or total sample size.

- Each of these industries have unique characteristics, and frontline employees working within them cannot be homogenised. Some frontline positions in manufacturing, for example, provide better pay, benefits, and security (depending on the sector, company size, relations with unions) than service sector jobs, which are often characterised as precarious work (a broad term used to describe working arrangements that are risky, temporary, part-time, insecure, uncertain, often provide low or unreliable wages, and typically lack benefits, rights, and other legal protections). These differences are critical in shaping the experiences of women working in each industry.

- A two-step cluster analysis was conducted to explore patterns of frontline employee rewards among UK frontline employees. The solution revealed two clusters: a “moderately dissatisfied” group (n = 1,463, 50%), and a “moderately satisfied” group (n = 1,476, 50%).

- Engagement was measured across three variables: including how often employees felt passionate, committed, and motivated about their work, on a 1-5 scale (1 being “never,” and 5 being “always”). A chi-square test of independence was conducted to explore the relationship between frontline employee satisfaction level and engagement in their work. The analysis revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 443.244, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (10.9) and moderately dissatisfied (-10.9) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- Intent to leave was measured on 1-5 scale (1 being not at all likely to leave, and 5 being very likely). A chi-square test of independence was conducted to explore the relationship between frontline employee satisfaction level and whether they would choose to work for their organisation again. The analysis revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 111.03, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (5.3) and moderately dissatisfied (-5.3) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- Commitment was measured across four variables: including agreement on “this company deserves my loyalty,” whether they’d “be happy to spend the rest of their career” there, whether they would recommend the company as a good place to work,” and whether they “feel a strong sense of belonging,” on 1-5 scale (1 being “strongly disagree,” and 5 being “strongly agree”). A chi-square test of independence was conducted to explore the relationship between frontline employee satisfaction level and their commitment to the workplace. The analysis revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 651.50, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (14.2) and moderately dissatisfied (-14.3) groups differed significantly from what was expected. A logistic regression was conducted to examine the relationship between employee satisfaction and their commitment to the workplace. The model was statistically significant, suggesting that the moderately satisfied employees were 8.8 times more likely to perceive fairness compared to those with low satisfaction, Exp(B) = 8.77, 95% CI [7.34, 10.48], p < .001.

- Mignon, K. (2024). Employee jobs paid below the real living wage 2024. Living Wage Foundation.

- The current state of low pay in the UK. (2025, February 27). Living Wage Foundation.

- Employees were asked what the hourly wage of their primary job was (before taxes) on a sliding scale from “£0-9.99” to “£35 or higher,” and/or what their income was last year (before taxes) on a sliding scale from “under £20,000” to “over £65,000). Our data reveal two distinct realities: while moderately satisfied employees see more consistent opportunities for financial advancement, the moderately dissatisfied remain stuck in cycles of stagnation. Among hourly workers, nearly half (49%) of moderately dissatisfied employees earn below £20 per hour, compared to 31% of those who are moderately satisfied. A similar divide exists for salaried employees, where 70% of the moderately dissatisfied earn less than £40,000 annually, versus 60% of their moderately satisfied counterparts. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the relationship between frontline employee satisfaction level and whether their hourly wage was below £20. The analysis revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,503) = 77.46, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (-2.9) and moderately dissatisfied (2.6) groups differed significantly from what was expected. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the relationship between frontline employee satisfaction level on whether their annual salaried wage was below £40,000. The analysis revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,436) = 15.19, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (-1.5) and moderately dissatisfied (1.8) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- Company-wide pay raises were asked with a yes/no response. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the relationship between frontline employee satisfaction level on whether they had received a company-wide pay raise. The analysis revealed a non-significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,437) = 1.61, p = .21.

- Merit- or performance-based raises were asked on a sliding scale between “50p or less” and “between £3-4 and hour” for hourly employees and “less than £500” and “between £4,000-5,000” for salaried employees, where they were asked how much their income increased. This was then dichotomised into above/below £1 hourly or £2,000 annually. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the relationship between frontline employee satisfaction level on whether they had received a merit- or performance-based raise larger than £1 hourly or £2,000 annually. The analysis revealed an association verging on significance, χ² (1, n = 163) = 3.94, p = .047.

- Lower wages were described as an hourly wage below £20 or an annual salary of below £40,000. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the frequency of men and women and their annual wage. The analysis revealed a significant association, χ² (3, n = 1,436) = 58.28, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed more women received a wage below £40,000 (53%; 3.1) than men (46%; -2.6) and differed significantly from what was expected. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the frequency of men and women and their hourly wage. The analysis revealed a significant association, χ² (3, n = 1,503) = 37.11, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed more women received a wage below £20 (55%; 1.8) than men (43%; -1.7) and differed significantly from what was expected.

- An ordinal regression analysis examined the relationship between hourly income and the likelihood that employees belong to the moderately dissatisfied or moderately satisfied group in relation to their total salary compensation. The model was statistically significant (χ² (6) = 121.68, p < 0.001), indicating that hourly income is a significant predictor of employee satisfaction. The analysis revealed a key threshold at an hourly income of approximately £20.00-24.99. Employees earning below this level were less likely to report satisfaction above the moderately dissatisfied range. As income rose beyond that point, increases in income were associated with only marginal improvements. In other words, while higher pay beyond £25/hour continued to have a positive effect, the gains in satisfaction diminished, pointing to a plateau. This highlights the need for a rewards strategy that goes beyond pay alone to include benefits, career growth, and professional development.

- An ordinal regression analysis examined the relationship between salaried income and the likelihood that employees belong to the moderately dissatisfied or moderately satisfied group. The model was statistically significant (χ² (10) = 34.09, p < 0.001), indicating that salaried income is a meaningful predictor of employee satisfaction. The analysis revealed a key threshold at around £36,000-40,000 per year. Employees earning below this range were less likely to report satisfaction above the moderately dissatisfied level. As income rose to or above this threshold, the likelihood of reporting moderate satisfaction increased. However, beyond this point, additional increases in income were associated with only minimal gains in satisfaction, suggesting a plateau effect. This reinforces the idea that while fair compensation is important, further improvements in satisfaction may depend on non-financial factors such as enhanced benefits, career growth, and professional development.

- An estimated 50% of frontline employees — or 8.4 million employees — fall into the moderately dissatisfied group. Of these, 61% (5.12 million employees) indicate they would not work for their organisation again, putting them at high risk of attrition. With an average turnover cost of £41,052 per employee (conversion from $52,000), the potential financial impact of this churn could reach £210.6 billion. By contrast, raising wages by £5 per hour (an additional £10,400 per year per employee, based on an average of 40-hours per week) for these 5.12 million at-risk employees would cost approximately £53.3 billion annually, across industries. However, this investment could yield substantial savings, as reducing attrition would offset these costs nearly fivefold, with every £1 spent on pay increases saving £5 in reduced turnover costs. Even a £5 per hour raise could result in a 5x ROI, making higher wages a financially sound strategy for improving retention.

- Universal Credit explained. MoneyHelper.

- Access to development resources was measured across eight categories: educational resources, flexible work, job-shadowing, mentorship opportunities, part-time work moving into full-time, promotions, skill-building assignments, and training for higher paying jobs, on a 1-5 scale (1 being “never,” and 5 being “always”). A one-way ANOVA was conducted to investigate the relationship between frontline employee satisfaction level and access to development resources. The results indicated a significant effect, F (1, 2,937) = 1,128.82, p < .001. Employees in the moderately satisfied group reported significantly more frequent access to professional development resources compared to those in the moderately dissatisfied group.

- A logistic regression was conducted to examine the relationship between employee satisfaction and their access to development resources. The model was statistically significant, suggesting that the moderately satisfied employees were 7.4 times more likely to access opportunities compared to moderately dissatisfied employees, Exp(B) = 7.40, 95% CI [6.29, 8.72], p < .001.

- A linear regression was conducted to assess the effects of receiving a series of development opportunities on the likelihood of belonging to the moderately dissatisfied or moderately satisfied frontline employee group. The model was statistically significant, F (6, 2,932) = 201.41, p < .001, and explained 29% of the variance (R² = .29). Among the predictors, promotion opportunities (B = .09, SE = .01, β = .20, p < .001), formal training for higher-paying roles (B = .04, SE = .01, β = .11, p < .001), skill-building assignments (B = .05, SE = .01, β = .11, p < .001), opportunities for part-time employees to move to full-time roles (B = .04, SE = .009, β = .09, p = .001), availability of educational resources (B = .04, SE = .01, β = .10, p < .001), and flexible work arrangements (B = .03, SE = .01, β = .07, p < .001) were the strongest predictors. In contrast, job shadowing (B = -.03, SE = -1.25, β = .21, p = .53) and formal mentorship programs (B = .02, SE = .89, β = .37, p = .44) were not statistically significant at p =< .001.

- Britton, J., Drayton, E., & van der Erve, L. (2021). Universities and social mobility. The Sutton Trust.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to development opportunities and the level of satisfaction between frontline employee groups. Development opportunities were calculated as the combined opportunities an employee had across promotion opportunities, access to skill-building assignments, job-shadowing, mentorship programmes, training for higher-paying jobs, educational resources, opportunities for part-time employees to move into full-time roles, and access to flexible work. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 625.95, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (12.1) and moderately dissatisfied (-12.2) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to promotion opportunities (measured on a 1-5 scale with 1 being “never” and 5 being “always”) and the level of satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 564.24, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (9.6) and moderately dissatisfied (-9.6) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to skill-building assignments (measured on a 1-5 scale with 1 being “never” and 5 being “always”) and the level of satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 426.16, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (8.1) and moderately dissatisfied (-8.2) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to job-shadowing (measured on a 1-5 scale with 1 being “never” and 5 being “always”) and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 258.89, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (7.5) and moderately dissatisfied (-7.5) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to mentorship programmes (measured on a 1-5 scale with 1 being “never” and 5 being “always”) and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 409.16, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (9.5) and moderately dissatisfied (-9.5) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to training for higher-paying jobs (measured on a 1-5 scale with 1 being “never” and 5 being “always”) and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 520.64, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (10.1) and moderately dissatisfied (-10.2) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to educational resources (measured on a 1-5 scale with 1 being “never” and 5 being “always”) and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 408.53, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (8.3) and moderately dissatisfied (-8.3) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to opportunities for part-time employees to move to full-time jobs (measured on a 1-5 scale with 1 being “never” and 5 being “always”) and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 281.19, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (6.2) and moderately dissatisfied (-6.2) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- From unsung heroes to quiet quitters. (2024). Flip.

- From unsung heroes to quiet quitters. (2024). Flip.

- Clear and fair promotion processes were averaged across three variables (including whether the company has clear standards for decisions, whether employees can seek clarification about a decision, and whether information is shared regarding how decisions are made) on a 1-5 scale (1 being “strongly disagree,” and 5 being “strongly agree”). A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between perceptions of clear and fair promotion processes and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 832.68, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (15.8) and moderately dissatisfied (-15.9) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- An individual-centred approach to promotion was averaged across two variables (including whether the company responds to individual circumstances when it comes to promotion and whether HR takes into account individual information) on a 1-5 scale (1 being “strongly disagree,” and 5 being “strongly agree”). A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between perceptions of an individual-centred approach to promotion and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 723.90, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (14.4) and moderately dissatisfied (-14.5) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A logistic regression was conducted to examine the relationship between employee satisfaction and their perception of clear and consistent promotion processes. The model was statistically significant, suggesting that the moderately satisfied employees were 12.2 times more likely to perceive clear and consistent processes compared to moderately dissatisfied employees, Exp(B) = 12.24, 95% CI [10.18, 14.73], p < .001.

- A logistic regression was conducted to examine the relationship between employee satisfaction and their perception of individualised promotion processes. The model was statistically significant, suggesting that the moderately satisfied employees were 9.3 times more likely to perceive clear and consistent processes compared to moderately dissatisfied employees, Exp(B) = 9.34, 95% CI [7.86, 11.10], p < .001.

- Manager fairness was averaged across three variables (including whether managers follow fair procedures in decision-making, they do not show favouritism, and they apply policies consistently) on a 1-5 scale (1 being “strongly disagree,” and 5 being “strongly agree”). A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between perceptions of managers treating team members fairly in relation to promotion opportunities and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,852) = 184.90, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (7.7) and moderately dissatisfied (-6.9) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- Manager support was averaged across 15 variables (e.g., helping their team progress towards their goals) on a 1-5 scale (1 being “never,” and 5 being “always”). A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between perceptions of managerial support for career development and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 1,852) = 316.01, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (9.7) and moderately dissatisfied (-8.7) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A chi-square analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between frequent access to flexible work (measured on a 1-5 scale with 1 being “never” and 5 being “always”) and satisfaction between frontline employee groups. The results indicated a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 230.20, p < .001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (5.6) and moderately dissatisfied (-5.6) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- Job demands allowing for work-life balance was measured on a 1-5 scale (1 being “strongly disagree,” and 5 being “strongly agree”). A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the impact of employee satisfaction on perceptions of whether their job demands allow for work-life balance. The analysis revealed a significant association, χ² (1, n = 2,939) = 483.28, p <.001. Examination of standardised residuals revealed the moderately satisfied (8.5) and moderately dissatisfied (-8.6) groups differed significantly from what was expected.

- A logistic regression was conducted to examine the relationship between employee satisfaction and their perception of managerial fairness in resource distribution. The model was statistically significant, suggesting that the moderately satisfied employees were 3.8 times more likely to perceive fairness compared to moderately dissatisfied employees, Exp(B) = 3.76, 95% CI [3.10, 4.57], p < .001.

- A logistic regression was conducted to examine the relationship between employee satisfaction and their perception of managerial support in the growth and development of team members. The model was statistically significant, suggesting that the moderately satisfied employees were 5.9 times more likely to perceive support compared to moderately dissatisfied employees, Exp(B) = 5.85, 95% CI [4.78, 7.16], p < .001.

- Pace, L. (2022). Gender imbalance at work continues. Quinyx.

- A series of relative importance analyses were conducted to examine the relative importance of variables on UK frontline employees’ sense of satisfaction with their base pay, benefits, professional development, advancement opportunities, and pay increases. These analyses required items on similar scales to be grouped together. The first analysis examined the items asked on an agreement scale (e.g., clear, fair, and individual-centred promotion processes, access to flexible work) where the regression model explained 65% of the variance in employee perceptions of promotion opportunities (R² = 0.65), indicating that the independent variables accounted for a substantial proportion of the variability in perceptions. The second analysis examined the items asked on an agreement scale related to supportive managerial experiences (e.g., managers were fair and consistent in their support) where the regression model explained 27% of the variance in employee perceptions of promotion opportunities (R² = 0.27), indicating that the independent variables accounted for a substantial proportion of the variability in perceptions. The third analysis examined items that asked about the frequency of experiences across various organisational factors (e.g., job growth and development opportunities), where the regression model explained 44% of the variance in employee perceptions of promotion opportunities (R² = 0.44), indicating that the independent variables accounted for a substantial proportion of the variability in perceptions. The fourth analysis examined items that asked about the quantity of supportive experiences with managers (e.g., supportive manager relationships), where the regression model explained 37% of the variance in employee perceptions of promotion opportunities (R² = 0.37), indicating that the independent variables accounted for a proportion of the variability in perceptions. Once normalised, the data were organised in terms of relative importance.

- In this analysis, we've evaluated the various actions highlighted in the report to understand their relative impact on frontline employee satisfaction. Rather than reporting every action, we've focused on those with the most significant impact. While all actions in this report contribute, some have a bigger influence on driving overall employee experience. The action with the highest impact is increasing organisational transparency in decision-making, with a 14% impact, followed by training managers to follow fair procedures in decision-making (13%). Other influential actions include providing clear and accessible promotion pathways for employees at all levels (12%), ensuring managers apply policies consistently (12%), and designing processes that balance job demands with employees' life needs and responsibilities (10%). Additionally, providing access to educational resources (8%), having clear standards for promotion decisions (8%), ensuring promotion opportunities consider individual circumstances (8%), enabling HR or talent management departments to understand employees’ individual goals and preferences (8%), and providing access to formal training relevant to higher-paying roles (7%) all play a role in improving employee satisfaction.

- The state of the UK frontline workforce 2024 report. (2024). Quinyx.

- Brassel, S., Van Bommel, T., & Robotham, K. (2022). Three inclusive team norms that drive success. Catalyst.

- Gilmour, S. (2025, February 17). April 2025 changes in employment law – what employers need to know. Harper James.